November 10, 2016

Walt Lubbers: Traumatic Arrest- We're doing it wrong

Cardiac arrest after trauma is different than cardiac arrest from a "medical" cause. In trauma, some amount of energy has been imparted to the body which has changed the body structure fundamentally- either the tank is empty (hemorrhage), the pump is broken (myocardial rupture), or the pump isblocked (tension pneumothorax, tamponade), or the brain is smashed to bits and we can't do much about that. In medical arrest, the overall structure of the body remains more or less the same, but it's not working- ie the pump is not pumping, but it's mechanically intact, and the tank still has blood in it, and blood can get back to the heart, and the idea behind CPR is that if you can push on the chest to get some blood flow going you might be able to do something to temporize the patient and give you time to correct the cause before the brain dies. In trauma, pushing on the chest does probably nothing. If you ran a traumatic cardiac arrest without ever doing a single chest compression, that would probably be OK, but you've gotta do the stuff that actually makes a difference.

Of note: most of these people won't survive, but neither do most medical arrests. The survival is actually within a few percentage points of each other (7% vs 5%). So some people will survive, but also, everyone deserves the chance to be an organ donor, so everyone deserves you starting a resus on them.

Start more, do more, stop earlier

There are basically 4 things that might help in traumatic cardiac arrest- relieving tension pneumothorax, controlling hemorrhage, give volume back, relieving traumatic asphyxia, and there's almost no way to know what is killing your patient on scene so you have to just treat it all. So when you arrive on scene and confirm the patient is unresponsive, you should:

-Control external hemorrhage with tourniquets or aggressive wound packing

-Aggressively manage the airway- BVM is OK if you get good rise and fall with good seal, but ETT would be ideal if there are 2 or more medics, or a well placed SGA in either medics or EMTs.

-Bilateral needle decompression of the chest with an appropriate needle (3 inch or longer needle, 14 G or bigger)

-Restore intravascular volume with IVF. If you had blood, that'd be great, but out there it's not really an option, and this isn't the time to be stingy with fluid. Get an IO fast (or IV if that's easy), and pound in a liter of fluid on a pressure bag (the locked BP cuff around the bag is pretty cool). If they come back you can replace some volume with red cells later.

AFTER you've done all these interventions, look at the cardiac monitor. If the patient is bradycardic or in asystole after you've done the interventions, their chance of survival is essentially nil, and you can terminate the resuscitation. If they are in PEA with HR > 40 or in VF/VT, that may be someone with a chance- the pump is trying to work- maybe it just needs more fluid or a little less air in the chest. So shock them if needed. Repeat needle decompression, pound another liter of fluid. Make sure hemorrhage is controlled, and transport these folks to the hospital.

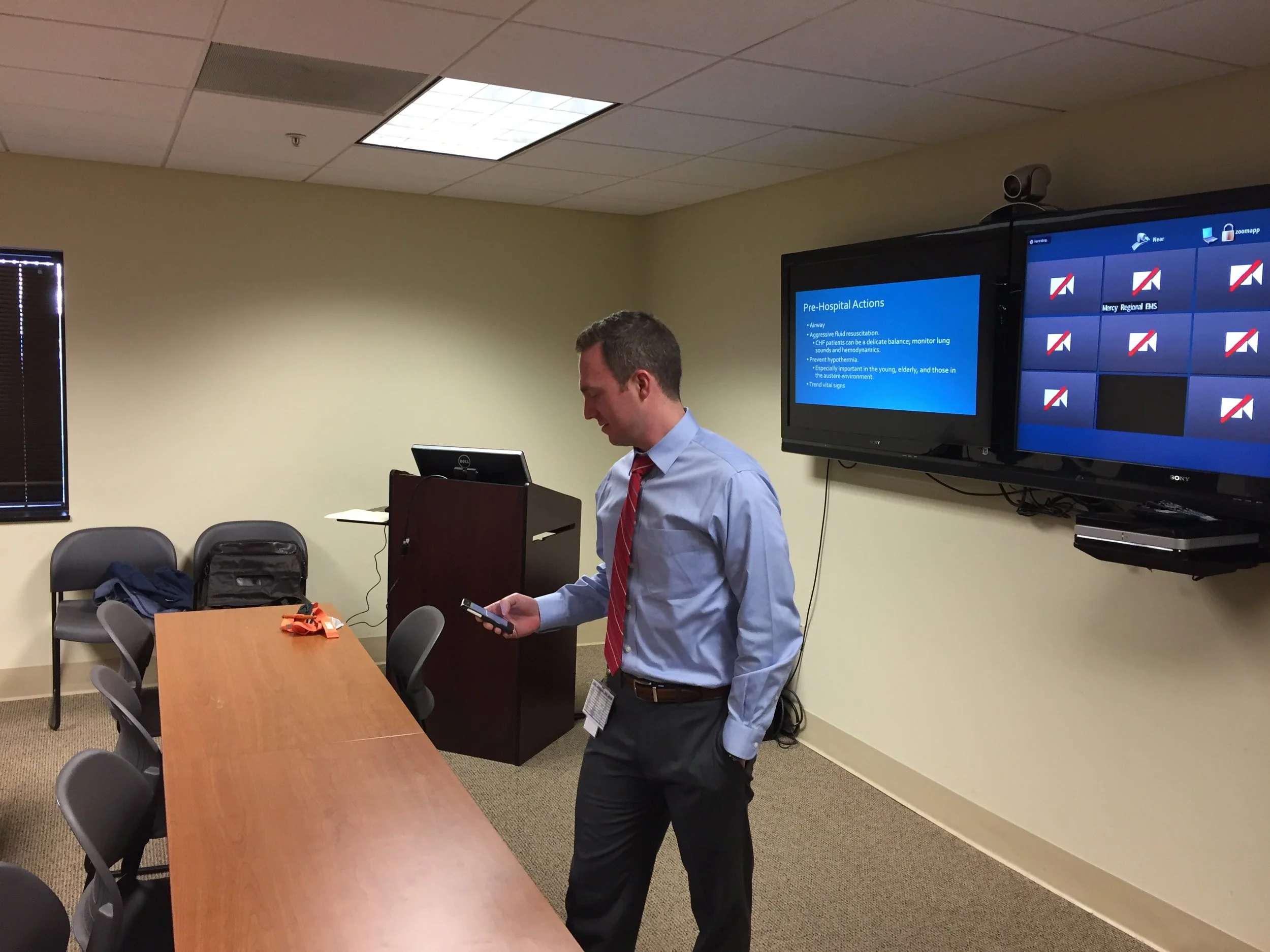

Molly Seidler, Jacob Shopp: Sepsis- what you do matters

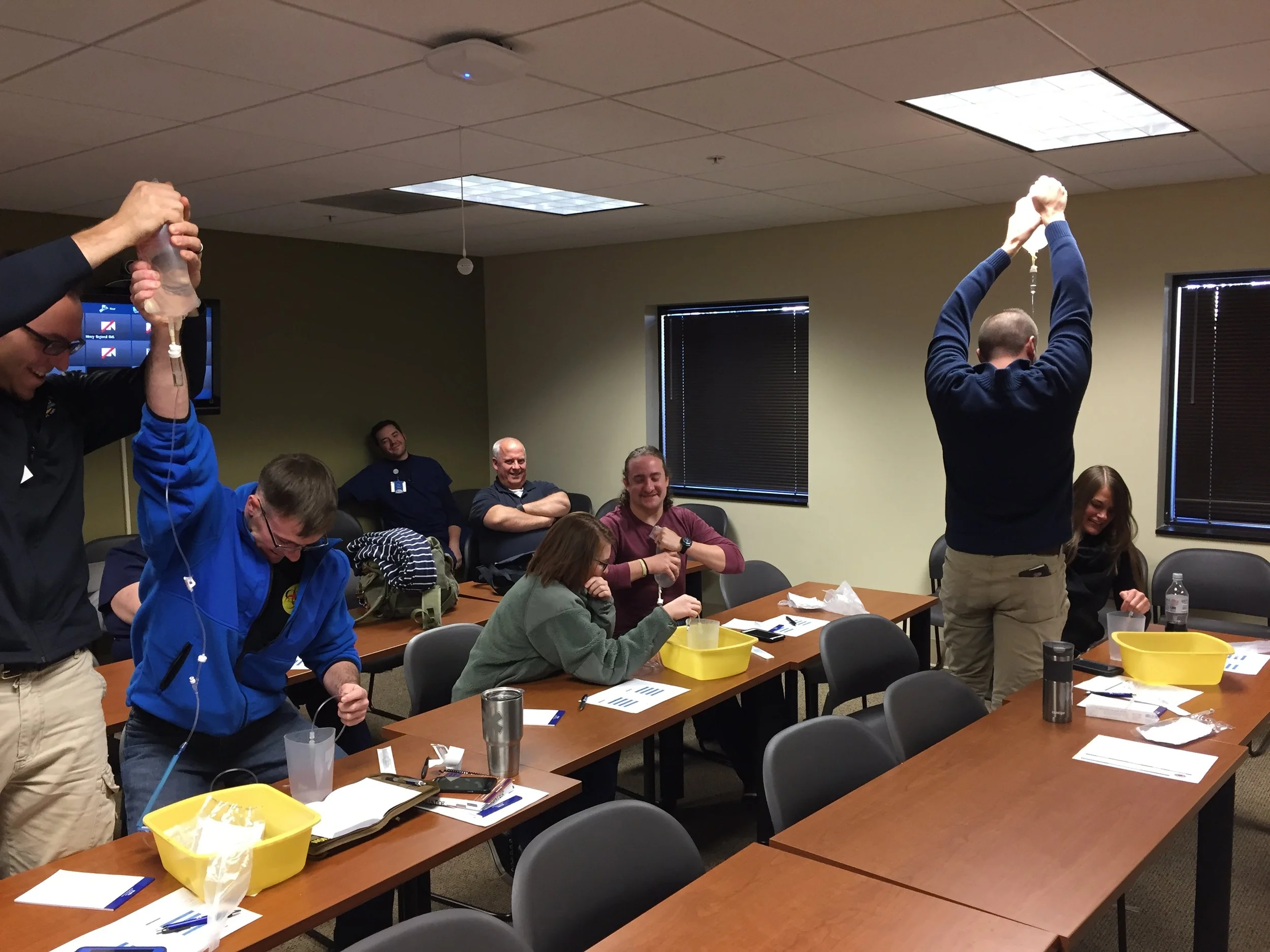

Sepsis is a pretty frequent in the EMS. About 1/3 of septic patients will come in through EMS. Recognition is the first step- just saying "sepsis" to the ED helps decrease mortality by up to almost 50%! These guys should get some fluid, even if they are CHF or ESRD (just monitor closely for fluid overload). An 18 g IV catheter has almost 10x the flow rate of a 22 g. But of course, you have to be able to get that 18....

Volume you can get through a 22g, 20 g, and 18 g IV catheter in one minute.

Landon Jones: Pediatric bits- things you should know about kids and their weird little bodies.

Kids have a smaller and anterior airway. Use of a combination beta agonist (albuterol) and an (ipratpropium), ie Duoneb, en route helps kids get better faster and may save the child an admission. Children usually aren't on opiates, but get into lots of them. A kid with depressed respirations and mental status should probably get some naloxone. How much? Who cares! (Editor's Note: The weight based dose is 0.1 mg/ kg) Go heavy on the dose in kids- they are opiate naive and will probably be fine if they get a milligram or two. Don't forget that opiate OD is an airway/ breathing problem. Before you reach for naloxone, you should be bagging these kids (and adults). Giving some PPV prior to naloxone might prevent post obstructive pulmonary edema as well, if you believe in it.

(Lubbers comment: To be fair, POPE does exist, and it happens when you take a dead person and suddenly make them not dead. Pulmonary edema also occurs as a result of opiate OD and respiratory depression. I'm not saying that no one gets pulmonary edema after resuscitation from opiate OD- I'm saying it's not the naloxone that causes flash pulmonary edema)

Jordan Cox: Neonatal Resus

Most newborns are fine, but sick ones are really frightening for everyone. APGAR scores are a measure of how the baby is doing, and you're looking for improvement- broadly, <3 is really bad, 3-6 is not great, 6-9 is OK. Resuscitation in a kid is warm/dry/ position 90% of the time. If not improving, give O2 at21-30% (just a little more than room air). If not better, then assist with BVM(HR<100). If HR drops below 60, do chest compressions. If not better fast, consider giving some epi (0.01 mg/kg bolus). A baby that's born at home that is not covered up is probably hypothermic. Act early- ventilate your babies.